Frank Lloyd Wright – the Heroic Age of Architecture

There’s a spare return ticket to Los Angeles; can you use it? It was just a couple of weeks before Christmas when Steve made me this offer, His original business flight had been changed at the last minute and at that time, the fact that we shared the same names allowed this flexibility.

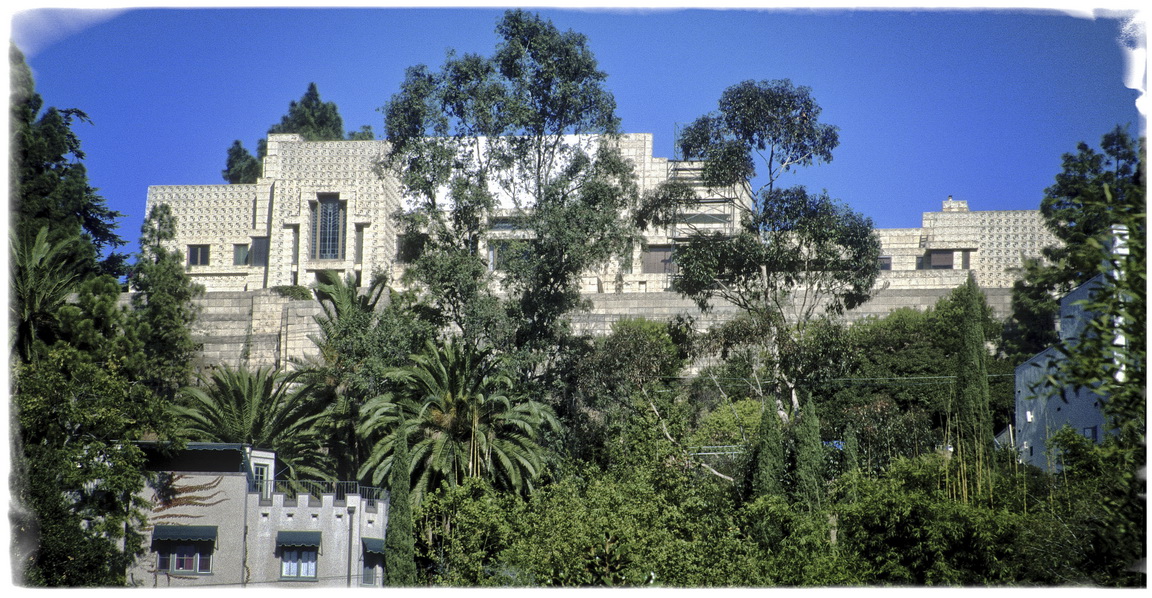

Looking back through my diary it seems I prevaricated for a while, but of course I jumped at the chance. Which is how I came to find myself cruising, perhaps crawling would be more accurate, around the narrow and twisted lanes of the Hollywood Hills with our host Craig doing the driving. And then quite unexpectedly “MASSIVE SURPRISE” we take a bend and come across a Frank Lloyd Wright masterwork – the Ennis House also known as the Bladerunner House.

Massive surprise because you understand such masterworks existed in my mind only in a sort of Valhalla of the gods. They could never exist in everyday life! But here we are and there it was The Bladerunner House a real Frank Lloyd Wright masterpiece.

Hindsight tells me that I really shouldn’t be surprised: after all, at the time, Craig and Linda lived in a very desirable modern house on one side of Canyon Drive in Hollywood. The very epitome of Des-res! And of course the area was littered with the works of eminent architects designed at around the time when tinsel-town was expanding. The Samuel Navarro House by his son was not far away, and both sides of the canyon itself had what was almost an exhibition of daring houses clinging onto or cantilevered out from the site.

The Ennis House seen from below: note the tarpaulin over a section of the main dwelling – clear evidence of a maintenance issue at that time

Canyon style: typical of the canyon style of house employing cantilevered construction and maximising the views over LA

The Samuel – Navarro House, in the Oaks, an exclusive area of Los Feliz, The house was designed by Lloyd Wright,’s son

I think that I must have been very lucky when I started as a student of architecture. It was an exciting time altogether not so long after the Second World War when British political life was full of building a New Britain and what could be. And although there was a depressing ‘sameness’ about much building taking place at that time, there was a surprising degree of agreement and enthusiasm about the likely way forward centred around certain prominent architects. There may not have been much certainty and agreement about “The Way Forward” but of enthusiasm there was plenty.

With hindsight I would have to say that those named architects were being called into use as often as not as “signposts”. The names of course were: Le Corbusier, Mies Van Der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright. They all represented a different architectural philosophy and the interesting thing is to what extent these philosophies still apply with no apparent agreement as to ‘Who Won’ in the architecture wars!

At that time the danger for an emerging architect or student of architecture would be to follow slavishly the aesthetic of his or her chosen idol. Something in fact that his chosen idol would never be prepared to do in his own right. But oddly, try as you might, somehow a pale imitation of FLW style never quite cut the mustard. There was something crucial missing and that something was Wright’s vision of architecture as an organic part of our world. But those were relatively idealistic times and little thought was given to what might have been seen as the darker side of such influential architects. And in any event the profession as a whole was concerned with higher things, with the main aim of building a new future in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War.

Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret), was a pioneer of modern architecture and a leader of the International Style. As an architect he was largely self-taught, but he was also a painter and writer of considerable merit. His writings for the most part explained his architectural philosophy to an intrigued public (Vers une Architecture) whereas it could be said that Lloyd Wright allowed his buildings to speak for themselves. Le Corbusier’s most celebrated buildings include the Villa Savoye outside Paris, Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France, and the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille.

In later life Lloyd Wright was known to rail against what he referred to as the glass box merchants but, on November 20, 1938, the Armour Institute of Technology held a gala at the Palmer House hotel in Chicago to celebrate its new head of the architecture program, Mies van der Rohe. Introducing him was Frank Lloyd Wright who wasn’t given to speaking well of his contemporaries. But on this occasion describing Mies, Wright said, “I admire him as an architect, and respect and love him as a man. Treat him well and love him as I do and he will reward you.” The rarity of publicly receiving Wright’s unqualified accolades underscored the brilliance of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and his place within modern architecture as one of the founders of the International Style.

Although to some extent it is true of all of the iconic buildings designed by these three masters, the work of Mies van der Rohe benefits by being presented in an uncluttered setting in order to carry over into the environment the clarity of thought and structure inherent in the building itself. The most successful photographs of the work of Mies rarely include people but concentrate on the building itself. Oddly enough, buildings whose very existence depend upon people rarely feature them in the photographs that showcase the building itself to the wider public.

The father of the expression “Less is more” cannot have intended that to exclude the very raison d’etre of his buildings.

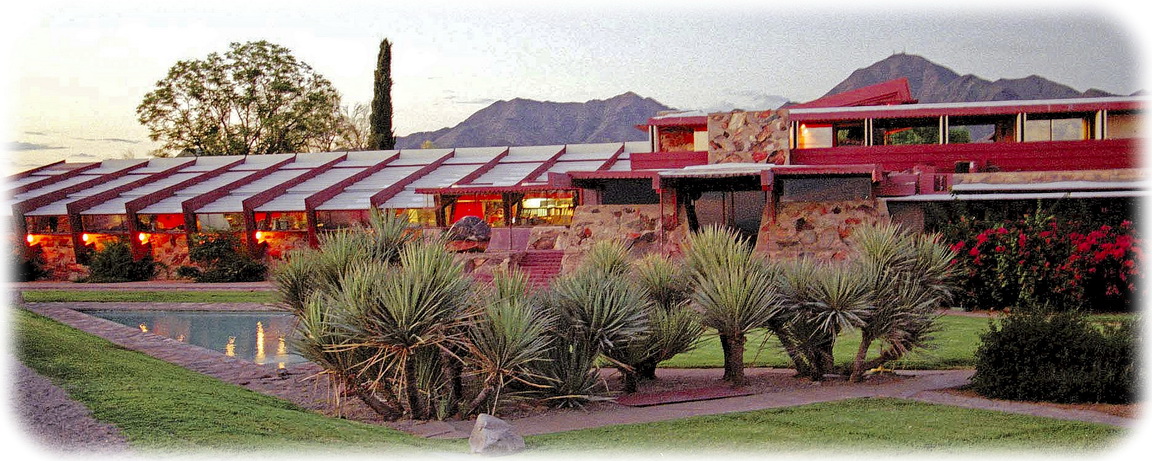

Lloyd Wright’s vision drew its inspiration very much from the location, the site and far from competing with the surrounding landscape, sought to be a natural part of the scenery and an organic extension of its surroundings. The Walker Holiday retreat on the shore at Carmel is probably an extreme example of this philosophy, but also Taliesin West in Scottsdale Arizona built by Wright and his followers as a retreat from the severe winters of the original Taliesin.

It is easy to criticise all of these master architects for a narcissistic obsession with the building as more of an expression of “their personal architectural vision” rather than the everyday quality that the client will expect in a house for living in. Here; Le Corbusier’s dictum “a house is a machine for living in” appears to acknowledge the correct priority that form follows function and not the other way round.

Nevertheless, Lloyd Wright’s clients went into the relationship with open eyes. It was a Frank Lloyd Wright masterpiece they were expecting together with the real estate value that they expected to go with it. And if over the years that aspect of the brief was less and less likely it was often because the commission succeeded more as a personal statement of Wright’s vision than it did as a domestic dwelling and often, as a consequence, the building was neglected with the result that maintenance suffered as did the perceived value. In many cases with Lloyd Wright’s Hollywood houses this functional ambivalence attracted the interest of film makers and the house was selected as a film set. The Ennis House, situated in the Hollywood Hills is often referred to as the Bladerunner House as a result of the Ridley Scott science-fiction movie of the same name which used the house as a set. Yet in many ways aspects of Wright’s life might be thought to be more dramatic than the most lurid of films.

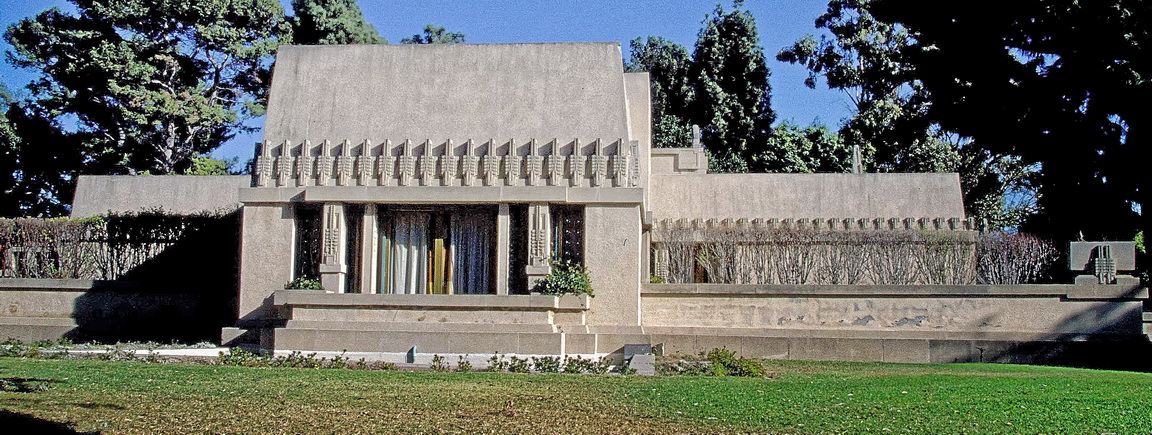

During the early years while practising in Chicago, Wright left his first wife with whom he had fathered six children and eloped with the wife of a client. On their return from Europe to which they had retreated to avoid the scandal, Wright set up home with Martha “Mamah” Borthwick Cheney, building a residence and studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin, named Taliesin in honour of the Welsh bard and in recognition of Wright’s Welsh roots. Wright cared little for the ongoing scandal and was quoted by a reporter as saying: “Two women were necessary for a man of artistic mind—one to be mother of his children and the other to be his mental companion, his inspiration and soul mate,” But Wright’s idyll was to be brought to a sudden end in the most shocking way. While Wright was on business in Chicago, Wright’s partner and her two children were taking lunch with a number of workers from the estate when one worker, Julian Carlton, who had been due to serve them, then ran berserk with an axe and killed Cheney, her two children and four others. Carlton later, while in custody, drank acid and died. Grief stricken, Wright threw himself into his work, completed Taliesin and spent the next decade building the luxurious Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. It appears that adversity brought the best out of Wright and he was soon to be engaged in a number of commissions for wealthy clients in Los Angeles, where his son already had a flourishing practice. His first Californian commission was the Barnsdall House also known as the Hollyhock house which was named after his client’s favourite flower. Wright was given a free hand by his client and no doubt repaid her by incorporating the hollyhock motif as a feature featured throughout the building.

Unfortunately over the years the building fell into a state of disrepair but more recently was donated to the city by the owner and is now the Barnsdall Art Park. Wright was distracted by his parallel commission in Tokyo and was fired and replaced by Rudolf Schindler towards the end of the contract. Schindler was a modernist and from time to time a student with Wright. His Lovell Beach House at Newport Beach also shares a prominent place in the development of the modernist style in Southern California. Wright trod his own path inspired largely by a re-working of ancient Mayan ceremonial architecture. While the Lovell House or Lovell Health House, also in the Hollywood Hills, is an International style modernist residence designed and built by Richard Neutra between 1927 and 1929 which with its steel frame can in many ways be acclaimed as the most advanced modernist house of them all. The house was used in the 1997 film L.A. Confidential.

Most of Wright’s homes were for wealthy clients but, devoted to the idea of providing beautiful yet affordable homes for the public, earlier in his career he had made attempts to design modest system built homes, and had entered into a business relationship with the Richards Company to market the homes. Richards allowed only approved contractors to build the houses, but Wright fell out with Richards owing to non-payment of royalties and the project was terminated. It is thought that some twenty five of these houses were built in all but fewer than fifteen are thought to survive,

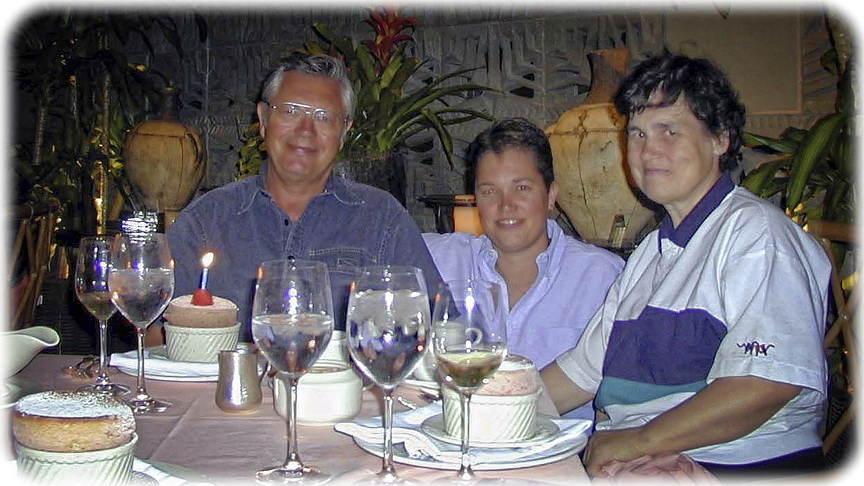

Much later during a rare two week break in the States, accompanied by my wife and daughter, Andree, I was fortunate enough to pay a visit to Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s winter home and school in the desert from 1937 until his death in1959. Today it is the main campus of The School of Architecture at Taliesin and houses the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and is generally accepted to be one of the most successful of Wright’s works in a long career. The icing on the cake was to come only a day or so later when we all celebrated my birthday by dining in the Frank Lloyd Wright Room at the Arizona Biltmore Hotel. The hotel was designed by Albert Chase McArthur (brother of the hotel owner), but is often mistakenly attributed to Frank Lloyd Wright, due to Wright’s on-site consulting for four months with regard to the “Textile Block” used in the hotel’s construction.

They do say that those who “can” “do”, while those who can’t “teach”! Which could explain why many young architects out of schools of architecture revere the big named architects, for it’s those architects that their teachers would aspire to be themselves (if only). But the architecture of the future must surely have its feet well and truly on the ground, and be less occupied by “big names” while reflecting the environmental and green issues facing the world today. Perhaps someone like Yasmeen Lari, who was awarded the prestigious Jane Drew Prize in London in March 2020, an award that recognises women’s contribution to architecture for her tireless humanitarian work over the last two decades. And goodness knows what Covid 19 will do to the economy and what style of architecture will emerge as a consequence. I would like to think that the new architecture will be much more socially responsible and that houses will be thought to be less a capital asset and more an essential social need. But if money rules as it usually does we may not be so fortunate and yet another opportunity will be squandered.

All photographs by the author Steve Mitchell; with acknowledgements to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation for the Taliesin West photographs